- Welcome to Conscious Breath Adventures

What Do Humpback Whales Eat? Part 4: Herring

- Home

- Humpback Whales

- What Do Humpback Whales Eat? Part 4: Herring

How Do You Like Your Herring?

by Cloe Waterfield

Finally, in our series on What Do Humpback Whales Eat, a fish we all know and may have even met personally: the herring. But before we dive into the life of the herring, how about an old joke?

Father: “What hangs on the wall, is green,… and whistles?”

Son: (long pause…) “… I give up.”

F: “A herring.”

S: “A herring doesn’t hang on the wall!”

F: “So nail it there.”

S: “But a herring isn’t green!”

F: “So paint it.”

S: “But a herring doesn’t whistle!”

F: “Right! I just put that one in to make it hard.”

But seriously, as we will see, like many of the other things humpbacks eat, they are a versatile little fish. Herring are a major prey item for humpbacks in the north Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. There are three species in in the family Clupeidae, but most abundant is the Atlantic herring, Clupea harengus.

They are a silvery fish, up to 18” long, with a protruding lower jaw, one dorsal fin and no lateral line. They also hate bubbles and have a defensive habit of balling up in large schools. These traits have been successfully exploited by humpbacks who have developed specific and refined feeding techniques to corral and catch them called bubble net and bubble cloud feeding.

They are a silvery fish, up to 18” long, with a protruding lower jaw, one dorsal fin and no lateral line. They also hate bubbles and have a defensive habit of balling up in large schools. These traits have been successfully exploited by humpbacks who have developed specific and refined feeding techniques to corral and catch them called bubble net and bubble cloud feeding.

Herring are filter feeders and migrate up and down in the water column, following their planktonic prey. They are a significant fishery resource for humans too, both for food and lobster bait. Stock management is important and, as we learned in the last article on menhaden, it’s critical to consider all species that depend on and consume herring when setting catch limits.

Here are five things to know about herring:

- You can probably mix and match some names a little and still be okay

Young herring are called sardines. But some species of pilchards are also called sardines. There are a number of other species called sardines. And many other species are also called herring, too. There’s the graceful herring or the Sanaga pygmy herring and more. And, as Shakespeare put it in Twelfth Night: “Fools are as like husbands as pilchards are to herrings; the husband’s the bigger”.

- There are such things as wise, old herring

I am able to make this statement because herring can reach 18 years in age, which seems pretty long for a small forage fish. And, while they may appear simple, they actually employ quite sophisticated feeding and defense strategies.

An example is ram feeding on copepods. If a school of herring meets an aggregation of these planktonic animals they will open their mouths wide and ‘ram’ through it. The herring maintain separation from each other equivalent to the jump length of a copepod and it’s this teamwork that is exceptional. The copepods jump out of the way, but they eventually tire. With the herring working in a synchronized fashion, spread out in just the right positions to nab the exhausted zooplankton, it pays off for the fish.

- They are also quite popular

So popular, in fact, that fishers from far and wide came to the eastern North Atlantic to catch them but by the mid 1960’s they had wiped out the fishery. With the subsequent passage of various Fisheries Acts, numbers have recovered, but concerns still remain.

Herring management is sophisticated;  it takes into account their value to ecotourism endeavors – as a prey item for whales and dolphins – and even assesses the reproductive status of the fish. By determining the gonadosomatic index (the ratio between the weight of the herring’s ovaries to its overall body weight) managers can close the fishery when the herring are about to spawn.

it takes into account their value to ecotourism endeavors – as a prey item for whales and dolphins – and even assesses the reproductive status of the fish. By determining the gonadosomatic index (the ratio between the weight of the herring’s ovaries to its overall body weight) managers can close the fishery when the herring are about to spawn.

This is important because, while it seems that adults are not currently being overfished, not enough young are being born. The spawning stock biomass is well below where it should be. Recruitment has been dropping since 2013 and 2016 was the lowest ever recorded.

But they continue to be fished heavily, even in and around feeding humpback whales. We’ve seen this firsthand in the Bay of Fundy where herring boats, which work at night, will come directly into the area where the local whale watch operators saw the whales that day. It seems as if the herring fishers were watching and listening to the whale watchers on the radio to learn the location of the whales which in turn know the location of the herring. Due to overfishing, earlier this summer (2019), all herring fisheries operating out of southwest Nova Scotia, where the Bay of Fundy is located, lost their sustainability rating.

But they continue to be fished heavily, even in and around feeding humpback whales. We’ve seen this firsthand in the Bay of Fundy where herring boats, which work at night, will come directly into the area where the local whale watch operators saw the whales that day. It seems as if the herring fishers were watching and listening to the whale watchers on the radio to learn the location of the whales which in turn know the location of the herring. Due to overfishing, earlier this summer (2019), all herring fisheries operating out of southwest Nova Scotia, where the Bay of Fundy is located, lost their sustainability rating.

- But not as popular as lobster

The lobster industry needs a lot of bait, and lobster love herring. But low numbers and restrictions in the herring fishery have driven lobstermen to alternatives. The lobster industry in Maine (which is the epicenter for US lobstering at around 80% of the $500 million annual catch) is the most valuable single species fishery in the United States.

With herring in short supply the industry has gotten creative. Bait alternatives include menhaden, another forage fish targeted by humpback whales, from as far as the Gulf of Mexico. Even Uruguay can compete as a bait source, sending the blackbelly rosefish, a species just approved, all the way to New England. Other esoteric but perhaps more sustainable options include pig skin and cowhide (hairless if possible, lobsters apparently suffer from hairballs).

Scientists are also looking at a potential win-win. If cleared from the risk of spreading disease, Asian carp, an invasive species in the Illinois River and Great Lakes, would be a viable substitute. All these mean more herring for humpbacks but also serve to illustrate how our simple appetite for lobster can have broad impacts in many far flung locales.

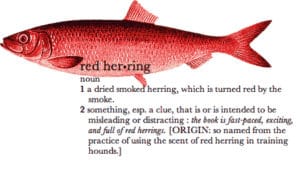

- Finally, what about that red herring?

Our British readers will remember a wonderful TV game show called Call My Bluff. Teams theatrically presented definitions of quite esoteric words, one of which was correct while two were red herrings – seemingly believable but entirely false.

A red herring is a logical fallacy, a narrative designed to lead you away from the truth. Examples abound in classic crime literature like Agatha Christie novels. But red herrings also pop up frequently these days in our current  age of whacky politics and fake news.

age of whacky politics and fake news.

The origin of the term “red herring” is ascribed to a William Cobbett who in 1803 claimed in the British press that as a child he’d used a super-smoked (hence red) herring to draw hounds away from the scent trail of a fox. He presented this example to illustrate the laziness of the rest of the Press saying it was easy to lure them down a completely erroneous course of reasoning.

Whether that explanation is itself is a red herring is debatable but I do think the following has merit:

“Why do fish ignore you? Because they are hard of herring!”

Red and deaf or old and wise we are grateful for these interesting and important little fish that sustain humpbacks and so much more. Now, by Part 4 of this series, it is easy to see the thread of interdependence woven between some of the largest creatures in the ocean and some of the smallest.

Continuing in this vein, next time we’ll wrap up our series on whale diets with a look at something that doesn’t have fins: krill

Sources:

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/c45d/222da3183ce8e93a222bd6b00472315f3869.pdf

http://www.asmfc.org/files/KidsTeachers/2014FishFactSheets_reduced.pdf

http://dlc.dlib.indiana.edu/dlc/bitstream/handle/10535/2796/considering.pdf?sequence=1

http://www.asmfc.org/uploads/file/5cddb296Atl.HerringDraftAddendumIIFinalApprovedRevised.pdf

http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/fm-gp/sustainable-durable/fisheries-peches/herring-hareng-eng.htm

https://www.savingseafood.org/news/international-trade/atlantic-canadian-herring-fisheries-lose-sustainability-label/

https://www.wbur.org/earthwhile/2019/05/28/lobster-bait-herring-shortage-fisheries