- Welcome to Conscious Breath Adventures

What Do Humpback Whales Eat?

Part 1: Capelin

- Home

- Conservation

- What Do Humpback Whales Eat? Part 1: Capelin

What Do Humpback Whales Eat?

by Cloe Waterfield

Have you ever wondered how humpback whales develop and maintain those 40-ton physiques? Please join us as we meet the much smaller and humbler creatures that humpbacks consume in rather large numbers. Individually they are not quite as charismatic but the ocean ecosystem, and even national economies, depends on them. They deserve some airtime.

During our time seeing and swimming with whales in the Caribbean each winter they are on their annual fast. They do not eat for several months each year. So while we do get to see all their amazing breeding-related social behaviors, we don’t see them feed.

And humpback whales are famous for their spectacular feeding techniques. Like blowing bubbles to herd prey, lunge feeding and lobtail feeding (herding up schools of fish). Many people wonder if they can swallow a human [The answer is no, they have very small throats. They don’t even have teeth!]. There’s a lot to learn. But we’re going to save how they eat for a later post and focus now on what they eat. (photo: Bob Bartlett, TrinityEcoTours.com)

Part 1 – The Capelin

To kick things off we’ll start with the capelin, Mallotus villosus. Capelin are not a well known fish like cod or grouper, but for humpback whales they are one of the big 6 (sand lance, capelin, herring, menhaden, mackerel and krill).

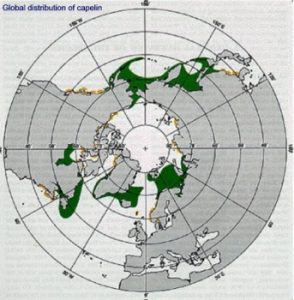

Capelin are small (around 6” long), slender, silvery fish that form large schools in northern waters. They are an Arctic species, found in the northern Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. They have pretty green backs, silver sides and fan-shaped fins. Capelin live about 5 years, leading a pelagic existence (mostly in the open oceans) eating plankton (like copepods, krill and amphipods). Capelin are a key food for humpback whales and other cetaceans and a critical one for cod – at times they comprise 90% of a cods diet. The health of commercially important fish stocks depends completely on this tiny schooling fish. (photo: Paul Souders, WorldFoto.com)

Here are 5 things you should know about the cute capelin:

- They come ashore to breed

Capelin roll on the shore in Witless Bay, Newfoundland. (Photo: Kate St. John)

Capelin are famous for the ‘roll’. This is not a sushi roll. The capelin roll is an annual event. In Newfoundland it generates a festival atmosphere (advertised on tourism websites) as people wade out and scoop or net buckets of the small fish. Humpback whales will come close in to shore after them, as will as fin and minke whales. Scientists can predict the number of whales based on the number and density of the capelin aggregations.

- You may have eaten their eggs

You may think you’ve never met a capelin personally but if you’ve ever tried sushi with the orange fish eggs (roe) there’s a good chance you’ve eaten it.

Traditionally the roe is from a flying fish, called tobiko, but roe from the capelin, known as masago, is also common (and often cheaper). The roe is harvested from female capelin before they spawn. Capelin eggs are an important fishery product from Canada and Iceland.

- They are being tracked by citizen scientists all around Atlantic Canada.

Supported by the World Wildlife Fund this project is a great example of how smartphone technology and an informed public can be used to help conservation efforts.

As capelin are so important as a forage fish for other species like cod, seals and whales, scientists are asking the public to report their observations of rolling capelin. Knowing where they are spawning can help protect that critical habitat.

The project is focused in Canada on the Gulf of St Lawrence, Newfoundland and Labrador and you can track it in real time as it progresses around the bays. Check out www.ecapelin.ca.

- Capelin and smelly fish oil

Capelin is also one of a number of species that is caught and rendered into fish oil for the nutritional supplement industry to get your omega 3’s. Up to 80% of capelin caught are rendered as fish meal for animal feed.

Capelin was once processed into Asian fish sauce at a plant in Newfoundland in the early 2000’s. They’ve since closed the facility but the smell from the leftover fermented fish is so bad that visitors have to check the wind direction before getting anywhere near it. It sounds funny but for the residents of St Mary’s it’s a million dollar environmental clean up which the town just cannot afford. And if the facility flooded or the roof failed and the vats spilled, the entire town could face evacuation.

- They migrate too

In common with their much larger predators, humpback whales, capelin undertake a migration themselves, accordingly sized. Around Iceland they’ll spawn in coastal areas in the spring and early summer then head offshore to feed. After feeding in northerly waters in the summer, just like the humpbacks they head south for the winter and hang out until its time to breed.

Capelin and Climate Change

The geographic range of capelin, and hence cod, whale and seabird populations, is tied to ocean temperatures. They’ve been described as a canary for climate change. As Arctic seas are warming faster than all other marine habitats, ocean temperatures and circulation are changing with far-reaching consequences. The Icelandic capelin fishery was closed this year because of low stock numbers which has serious implications for the whales. Also recently in the news was a die off of seabirds (especially tufted puffins) from the Barents Sea. The birds starved to death. With little ice to melt and kick off a spring explosion of phytoplankton, the result was simply not enough fish for the birds to eat.

Fisheries and Whales

Additional food for thought is the relationship between fishing and whales. Scientists have in past years been able to accurately predict cod and whale abundance based on capelin numbers. They have estimated the enormous numbers, over 2 million tons, of capelin that humpbacks consume.

Bearing in mind that capelin and cod are an important economic resource, the complicated and emotionally charged issue of Iceland’s recently-resumed whale hunt gains layers of complexity. There are conflicts at times between fishers and whales, both competing for the same resources. And, since the whaling moratorium, humpback numbers have increased while fish stocks have not.

Just last week Iceland announced a shrinking of the economy. Based partly on, you guessed it, the failure of the capelin stock….

It definitely seems that the humble capelin is actually far more interesting than it might sometimes be given credit for.

I hope you will continue to follow our series as we learn more of the back-story on the diet of humpback whales. Next time we’ll meet the sand lance, an evasive little fish that spends much time buried in the sand. But is a critical food, especially for whales in the Gulf of Maine.