- Welcome to Conscious Breath Adventures

Humpback Whales and Ship Strikes

Report on a Special Edition of the Journal of Marine Biology

I was planning on something a little more lighthearted this week, maybe some fun whale facts and crafts for our younger whale-lovers. But, then the MARMAM digest arrived which included a link to a special edition of the open access Journal of Marine Biology, devoted to cetaceans; Protecting Wild Dolphins and Whales: Current Crises, Strategies, and Future Projections.

I was planning on something a little more lighthearted this week, maybe some fun whale facts and crafts for our younger whale-lovers. But, then the MARMAM digest arrived which included a link to a special edition of the open access Journal of Marine Biology, devoted to cetaceans; Protecting Wild Dolphins and Whales: Current Crises, Strategies, and Future Projections.

Guest editors Lori Marino, Frances Gulland, and Chris Parsons have compiled six articles covering what we know about some of the most pressing issues in cetacean conservation.

As background to this special edition they offer a reminder why a focus on conservation is timely and necessary; “At a time when the problems cetaceans face are converging with a myriad of other issues, the possible approaches to be employed to mitigate these problems require unprecedented flexibility and sophistication.”

The Earth just lost another species: the Baji river dolphin. Whale stocks are struggling in many regions, and the dangers from ship strikes, trash and debris in the oceans and even whale watching are increasing. Plus, we know more about cetacean society than ever before. Cetaceans have culture, families, share knowledge and have even been declared non-human persons. The editors point out that for these reasons, our protection efforts must also take psychological issues into consideration.

The articles are through and enlightening reads, available in full online. One of the studies, a summary of whale-vessel collisions in Alaska, was particularly interesting. Here are a few of the key points.

The articles are through and enlightening reads, available in full online. One of the studies, a summary of whale-vessel collisions in Alaska, was particularly interesting. Here are a few of the key points.

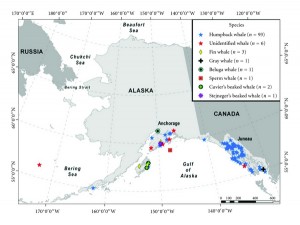

The authors analyzed records of collisions with whales in the waters within 200 nautical miles of Alaska, to glean some statistics and possible ways to reduce this sad result of increased human incursions into the marine environment.

Of the 108 usable records some trends were recognized. Most incidents (86%) involved humpback whales. Not surprisingly most occurred in the summer (feeding) months and collision reports increased towards the end of the time period, 1978 – 2011.

Not all strikes killed the animals; only 25 records were known to have resulted in death. Blunt force injuries were three times more common than sharp trauma injuries (that physically cut the animals, like propeller wounds). Indeed some of the injuries described make disturbing reading and in about a third property damage or injury to humans was also entailed.

In 15 cases, whales struck anchored or drifting boats – clearly sound plays a part in enabling them to avoid vessels. And one sentence jumped out in particular in reference to what the boats were doing before the incidents: “2% were intentionally ramming whales.” Good lord.

The real take home message is the need for boater education and better reporting. The 100 or so incidents assessed are probably just the tip of the iceberg. And confounding the lack of reporting (3 out of 4 collisions are possibly never mentioned) is the absence of a standardized collision reporting form. This is important.

As the authors note: “Most of these (anecdotal) reports lack so many critical details such as vessel speed, location, and the fate of whale that although they would contribute to a better understanding of the true frequency of whale-vessel collisions, they might not advance our knowledge of the specific factors leading to collisions or their outcomes.”

Ship strikes are typically reported on a form designed for marine mammal stranding events and yet our National Marine Mammal Stranding Database does not accept ship strike records. Urgently needed is a proper standardized reporting form for collisions so that all salient details such as vessel size, speed, location, etc. are recorded and we can apply the knowledge gleaned to make better management decisions.

In addition, boaters need to be better educated about the risks and how to operate safely particularly in whale ‘hot-spots.’ While this study focuses on Alaska, the lessons are applicable anywhere we share our coastal waters with marine mammals.

For more information on ship-strikes and boat speed zones see NOAA’s ship-strike reduction program. The Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society prepared a report on the issue, which is available for download. And for smart phone users going boating in right whale habitat in the Atlantic region, don’t forget there’s an app for that, available on iTunes! Alaska, Humpback whales, Journal of Marine Biology, marine mammals, Ship strikes